Fragility Forum 2018: Can security sector reform prevent conflict?

This article was first published on the World Bank Development for Peace blog and is reproduced here with kind permission of its co-authors, Bernard Harborne and Paul M. Bisca, and the World Bank.

Consider some figures: In 2016, the world spent almost US$1.7 trillion on military expenditures, a number that included not only weapons, but also pensions and salaries of personnel. By contrast, data from the OECD show that net official development assistance for the same year peaked at US$142 billion. In other words, countries spend over ten times more on war than aid in an era when about two billion people still live in places where violence is a threat to life.

Clearly, if we are to advance the SDGs, we need to tip the balance in favor of preventing violent conflict. During the World Bank’s 2018 Fragility Forum, the potential role of security sector reform (SSR) as an instrument of prevention was explored at a session organized by United Nations Department of Peacekeeping Operations (UNDPKO) and the Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces (DCAF).

At first glance, this conversation may seem better suited to blue helmets on the frontlines of conflict zones or diplomats negotiating peace agreements. But in shifting towards preventive action, we need to make security services operate by the same standards of accountability as other elements of the public sector. The Forum was a great example of bringing these diverse disciplines together and learning the different perspectives to understand how the security development nexus can be concretized. In that context, the role of economists and public finance experts in contributing to security sector reform was said to be a potential ‘game-changer.’

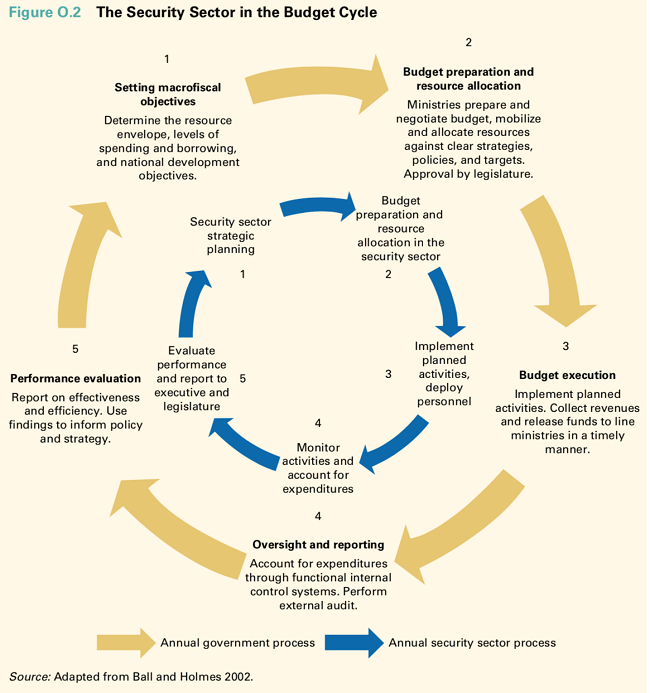

The reason is that defense, public safety, and justice functions usually carry a heavy fiscal burden and make up significant portions of national budgets. Therefore, by fully integrating the security sector in the budget cycle – through tried and tested tools such as public expenditure reviews – policymakers can assess if SSR efforts are affordable; if resources are allocated according to coherent policies; and if the effectiveness of security operations will be undermined or strengthened by resource management.

(Source: Harborne, Dorotinsky, & Bisca, eds. (2017). Securing Development: Public Finance and the Security Sector.)

The UN defines SSR as a process which strengthens the accountability of security institutions controlled by civilians, and operating according to human rights and the rule of law. SSR brings together soldiers, judges, police and civilians to elicit coherent national security strategies that promote greater transparency, effectiveness, and accountability. This work is both technical and political, with challenges ranging from recruiting new grunts to empowering parliamentarians to exercise legislative oversight of the military.

Many countries affected by fragility have started focusing on expenditure analysis of security and justice actors according to recognized standards of public sector performance.

For example, a public expenditure review of security services undertaken by the World Bank in Afghanistan in 2005 revelated that security spending exceeded domestic revenues by over 500 percent, running at some US$1.3 billion per year, or just 23 percent of GDP. In 2012, a similar study undertaken by the United Nations and World Bank in Liberia estimated the total cost of providing security services during 2012-19 at US$712 million, an amount which even prior to the 2014 Ebola outbreak proved unsustainable. Meanwhile, in Somalia another joint study with the UN found that ensuring that payment systems can facilitate the transfer of stipends from donors to the national army was essential to guaranteeing security for development.

Middle-income countries affected by high levels of homicides also face similar challenges. In 2012, a study in El Salvador found that there was little coordination and among police, courts, and executive institutions responsible for citizen security planning. This increased vulnerabilities due to corruption because of weak performance measurement. Meanwhile in Mexico, spending on citizen security (comprised of defense, public safety, and justice) outweighed health and education as a percentage of executed expenditures in 2015.

Understanding the economic and financial dimensions of security and justice – recently examined in the “Securing Development: Public Finance and the Security Sector” sourcebook – rests on a simple, but powerful axiom: that SSR efforts to build better security and justice for citizens should be driven by data and hard evidence. Thus, by helping soldiers and diplomats decipher the economic and financial intricacies of security and justice, international financial institutions can fill a small, but crucial piece of the prevention puzzle.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on Linkedin

Share on Linkedin Share on Twitter

Share on Twitter