Fishing through oceans of data: security governance and artificial intelligence

From anticorruption bots to robotic police dogs , AI tech is becoming increasingly interesting for security governance actors. One field leaping ahead is maritime security governance.

To pick out a strategic yet troubled maritime domain, the Gulf of Guinea is the stretch of the mid-Atlantic between Senegal and Angola. High above, satellites watch the lively traffic of fishing fleets, counting around 1 500 large vessels crossing the expanse every day. Emitting signals from automatic identification systems beacons, the ships are also tracked by vessel monitoring services and digitalised registries note their identities. Altogether, this generates millions of GPS coordinates – a deep and swirling ocean of data that changes from season to season.

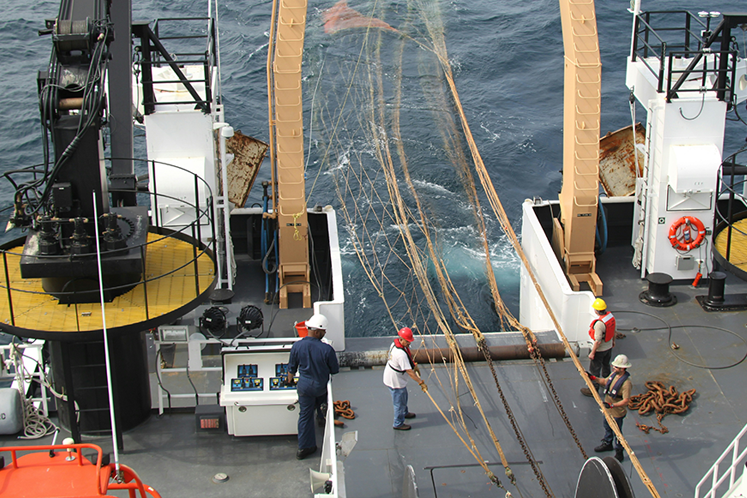

Photo: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

This dataset is highly relevant to the security of the humans and wildlife in the region. The Gulf of Guinea suffers very high rates of illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing (IUUF). This harms fisheries and endangers livelihoods, nutrition, and culture, making the behaviour of fishing fleets’ a real security concern for coastal communities and hinterlands.

According to fisherfolk in the Côte d'Ivoire, illegal fishing has a devastating ecological and economic impact, threatening food security and livelihoods and incentivising dangerous adaptation mechanisms, such trafficking and piracy. Indeed, recent DCAF research highlights illegal fishing as the maritime security issue that most affects Ivorians, and these problems cascade from threats to communities into threats to the region’s states.

The enormous amounts of data available on maritime activity is therefore critical, but the sheer amount poses a serious challenge. Watching the millions of geolocated data points tracking vessels across 2.4 million square kilometres is beyond what most regional navies can handle.

Interpreting the data heaps on further challenges because determining if a vessel is engaged in illegal fishing is not straightforward. Add in the fluidity of fleets’ behaviours, and the task becomes overwhelming. This challenge is not particular to the Gulf of Guinea, and is relatively common across global maritime regions.

This is a challenge that AI can help address. Over the last five years, the non-profit Global Fishing Watch and its coalition have built algorithms to monitor fishing and flag potential illegal activity. Its models draw on satellite images, data from beacons and onshore registries to gain an awareness of suspect vessels. Coupled with contextual knowledge, it can highlight both clearer and subtler cases of IUUF, such as potential trans-shipment incidents, even when one of the boats is ‘invisible’, with its beacon absent or switched off.

The algorithms’ ability to pull together multiple data sets is a huge advantage. “Automatic identification system or AIS is a great tool for understanding fishing activity,” according to Tyler Clavelle, Senior Data Scientist at Global Fishing Watch, “but we’re combining multiple data sources and models to get the most complete picture possible.”

These algorithms work much faster than humans alone and what’s more, they can synthesise missing data. Many vessels turn off their beacons, but from what the model has already learned from its training sets, it can still make predictions about the vessel’s nature and activity.

Photo: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

USING DATA FOR BETTER SECURITY

For the Gulf of Guinea and for maritime regions worldwide, the access to reliable and composite data is enormously beneficial for those trying to understand and counteract illegal fishing and other security problems that affect coastal communities. The pilot project with Global Fishing Watch and non-profit organization Trygg Mat Tracking in Senegal, Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire, and Kenya will provide satellite tracking data, analysis, and training needed to assess a fishing vessel’s recent operations and compliance risk.

Security Sector Governance professionals wondering how to use AI to their advantage can draw on practices pioneered by Global Fishing Watch and the wider coalition. One lesson is the power of bringing together different disciplines, including data scientists, AI specialists, biologists, governance experts and non-governmental organisations.

Photo: Jens Rademacher - Unsplash

Another is on the accessibility of the data. Global Fishing Watch publishes their data, even while they are careful not to allow ‘red flags’ to be mistaken for allegations. Data needs to be out there for it to do any good, and making it public allows for greater accountability. Therefore sharing data, within ethical frameworks, should be a basic principle for governance organisations venturing into AI.

The third lesson is about what AI can bring, and what it can’t. AI can help practitioners process an incredible amount of data, but it then needs to be fed skilfully into the policy process and into operations, in a way that reflects local conditions. This is where security sector governance experts like DCAF have an important role. With decades of experience supporting human-centred security policy and implementing reform operations, they can provide the expertise, the relationships, and the experience in inputting evidence that has been shaped by AI. For instance, using the data to help governments assess their maritime justice capacities, and then supporting them to adjust them to be more effective.

Indeed, AI has a lot to offer those interested in more effective and accountable security, be it on land or sea, and it is time for security governance professionals to properly embark in its application.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on Linkedin

Share on Linkedin Share on Twitter

Share on Twitter